Hey Guys Its Dangerous Down Here Go That Way Art

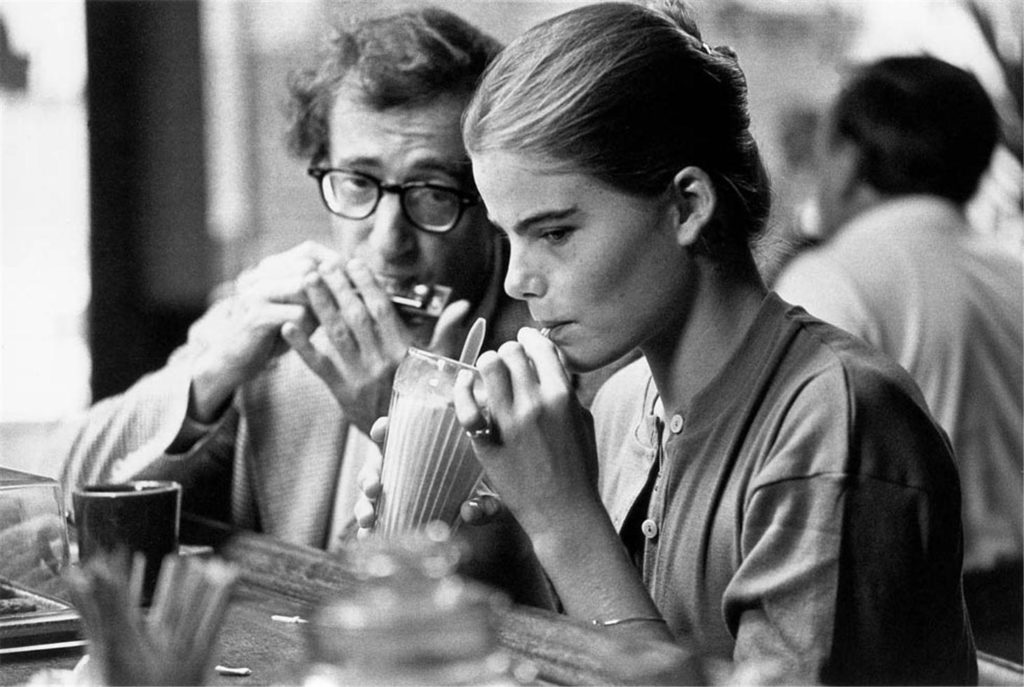

Still from Woody Allen's Manhattan

Roman Polanski, Woody Allen, Neb Cosby, William Burroughs, Richard Wagner, Sid Cruel, Five. S. Naipaul, John Galliano, Norman Mailer, Ezra Pound, Caravaggio, Floyd Mayweather, though if we starting time listing athletes we'll never stop. And what about the women? The list immediately becomes much more difficult and tentative: Anne Sexton? Joan Crawford? Sylvia Plath? Does self-harm count? Okay, well, it's back to the men I guess: Pablo Picasso, Max Ernst, Lead Belly, Miles Davis, Phil Spector.

They did or said something awful, and made something great. The awful thing disrupts the corking work; we tin can't watch or listen to or read the great piece of work without remembering the awful thing. Flooded with knowledge of the maker'southward monstrousness, we plow away, overcome past disgust. Or … we don't. We continue watching, separating or trying to separate the artist from the art. Either mode: disruption. They are monster geniuses, and I don't know what to do about them.

Nosotros've all been thinking nigh monsters in the Trump era. For me, it began a few years ago. I was researching Roman Polanski for a volume I was writing and found myself awed past his monstrousness. It was monumental, like the Grand Canyon. And yet. When I watched his movies, their beauty was some other kind of monument, impervious to my noesis of his iniquities. I had exhaustively read most his rape of thirteen-year-old Samantha Gailey; I experience sure no particular on tape remained unfamiliar to me. Despite this noesis, I was still able to consume his piece of work. Eager to. The more I researched Polanski, the more I became drawn to his films, and I watched them once again and once more—especially the major ones: Repulsion, Rosemary ' due south Babe,Chinatown. Like all works of genius, they invited repetition. I ate them. They became part of me, the manner something loved does.

I wasn't supposed to love this work, or this human. He's the object of boycotts and lawsuits and outrage. In the public's listen, man and work seem to exist the same thing. But are they? Ought we endeavour to carve up the art from the artist, the maker from the fabricated? Do we undergo a willful forgetting when nosotros want to listen to, say, Wagner's Ring bicycle? (Forgetting is easier for some than others; Wagner's work has rarely been performed in State of israel.) Or exercise we believe genius gets special dispensation, a behavioral hall pass?

And how does our answer change from situation to situation? Certain pieces of fine art seem to have been rendered inconsumable by their maker's transgressions—how can one watch The Cosby Show afterward the rape allegations against Nib Cosby? I hateful, patently information technology'southward technically achievable, merely are we fifty-fifty watching the show? Or are nosotros taking in the spectacle of our ain lost innocence?

And is information technology simply a matter of pragmatics? Do we withhold our support if the person is live and therefore might benefit financially from our consumption of their work? Practice we vote with our wallets? If then, is information technology okay to stream, say, a Roman Polanski movie for gratuitous? Tin can nosotros, um, sentinel information technology at a friend's house?

*

Only agree upward for a minute: Who is this "we" that's always turning upwardly in critical writing anyhow? We is an escape hatch. We is cheap. Nosotros is a manner of simultaneously sloughing off personal responsibility and taking on the mantle of easy authority. It'southward the voice of the middle-brow male critic, the one who truly believes he knows how everyone else should recollect. We is corrupt. We is make-believe. The real question is this: tin I beloved the art but hate the artist? Tin you? When I say we, I hateful I. I mean you.

*

I know Polanski is worse, whatever that means, and Cosby is more electric current. Just for me the ur-monster is Woody Allen.

The men want to know why Woody Allen makes usa so mad. Woody Allen slept with Presently-Yi Previn, the kid of his life partner Mia Farrow. Soon-Yi was a very young adult the offset time they slept together, and he the most famous film managing director in the world.

I took the fucking of Soon-Yi as a terrible betrayal of me personally. When I was young, I felt like Woody Allen. I intuited or believed he represented me on-screen. He was me. This is ane of the peculiar aspects of his genius—this ability to stand in for the audition. The identification was exacerbated by the seeming powerlessness of his usual on-screen persona: skinny every bit a kid, short as a kid, confused by an uncaring, incomprehensible world. (Like Chaplin before him.) I felt closer to him than seems reasonable for a lilliputian girl to feel about a grown-upwards male filmmaker. In some mad fashion, I felt he belonged to me. I had ever seen him equally one of us, the powerless. Postal service-Before long-Yi, I saw him as a predator.

My response wasn't logical; it was emotional.

*

One rainy afternoon, in the spring of 2017, I flopped down on the living-room couch and committed an human activity of transgression. No, not that i. What I did was, I on-demanded Annie Hall. It was easy. I just clicked the OK button on my massive universal remote and then rummaged around in a purse of cookies while the opening credits rolled. Every bit acts of transgression go, it was pretty undramatic.

I had watched the moving-picture show at least a dozen times before, just even so, information technology overjoyed me all over once again. Annie Hall is a jeu d'camaraderie, an Astaire soft shoe, a helium balloon straining at its ribbon. It'due south a love story for people who don't believe in love: Annie and Alvy come together, pull apart, come up together, and and so break up for good. Their relationship was pointless all forth, and entirely worthwhile. Annie'due south refrain of "la di da" is the governing spirit of the enterprise, the collection of nonsense syllables that give joyous expression to Allen's dime-store existentialism. "La di da" means, Nothing matters. It ways, Let's have fun while nosotros crash and fire. It ways, Our hearts are going to break, isn't it a lark?

Annie Hall is the greatest comic film of the twentieth century—amend than Bringing Upwards Babe, meliorate even than Caddyshack—because information technology acknowledges the irrepressible nihilism that lurks at the center of all one-act. Also, it's really funny. To watch Annie Hall is to experience, for simply a moment, that i belongs to humanity. Watching, you lot experience well-nigh mugged past that sense of belonging. That fabricated connection can be more beautiful than love itself. And that'due south what nosotros call great art. In case you were wondering.

Expect, I don't get to get effectually feeling connected to humanity all the time. It'south a rare pleasure. And I'm supposed to requite it upward just because Woody Allen misbehaved? It inappreciably seems fair.

*

When I mentioned in passing I was writing nearly Allen, my friend Sara reported that she'd seen a Little Free Library in her neighborhood admittedly crammed to its tiny rafters with books by and about Allen. Information technology made u.s.a. both laugh—the mental image of some furious, probably female, fan who just couldn't bear the sight of those books any longer and stuffed them all in the cute little house.

Then Sara grew contemplative: "I don't know where to put all my feelings well-nigh Woody Allen," she said. Well, exactly.

*

I told another smart friend that I was writing virtually Woody Allen. "I accept very many thoughts about Woody Allen!" she said, all excited to share. We were drinking vino on her porch and she settled in, the late afternoon light illuminating her face up. "I'm so mad at him! I was already pissed at him over the Soon-Yi thing, and so came the—what's the kid's proper noun—Dylan? Then came the Dylan allegations, and the horrible dismissive statements he made most that. And I hate the way he talks nearly Soon-Yi, e'er going on near how he's enriched her life."

This, I call up, is what happens to so many of united states of america when nosotros consider the work of the monster geniuses—we tell ourselves nosotros're having ethical thoughts when really what we're having is moral feelings. We put words around these feelings and phone call them opinions: "What Woody Allen did was very wrong." And feelings come from someplace more elemental than thought. The fact was this: I felt upset by the story of Woody and Presently-Yi. I wasn't thinking; I was feeling. I was affronted, personally somehow.

*

Hither'southward how to have some complicated emotions: sentinel Manhattan.

Like many—many what? many women? many mothers? many erstwhile girls? many moral feelers?—I take been unable to spotter Manhattan for years. A few months back, when I started thinking almost Woody Allen qua monster, I watched about every other movie he's ever made earlier I faced the fact that I would, at some point, have to watch Manhattan.

And finally the day came. As I settled in on my overnice couch in my comfy living room, the Cosby trial was taking place. Information technology was June of 2017. My husband, who has a Nordic flair for tranquillity drama, suggested I toggle between watching the Cosby trials and Manhattan so as to construct a kind of meta-narrative of monstrousness. Only my husband'south ascetic Northern European sense of showmanship came to naught, for the Cosby trial wasn't in fact televised.

Fifty-fifty so, information technology was out there happening.

The mood that summertime was one of extreme discomfort. Merely a general feeling of non-quite-rightness. People, and by people I mean women, were unsettled and unhappy. They met on the streets and looked at 1 another and shook their heads and walked away wordlessly. The women had had it. The women went on a giant fed-upwards march. The women were Facebooking and Tweeting, going for long furious walks, giving money to the ACLU, wondering why their partners and children didn't exercise the dishes more. The women were realizing the invidiousness of the dishwashing paradigm. The women were becoming radicalized, even though the women really didn't have the time to be radicalized. Arlie Russell Hochschild first published The 2d Shift in 1989, and in 2017 the women were discovering that shit was truer than e'er. In a couple of months would come the Harvey Weinstein accusations, and and then the free-fall grunter-pile of the #MeToo campaign.

Equally I wrote in my diary when I was a teen, "I don't feel smashing about men right at present." I yet didn't experience great about men in the summer of 2017, and a lot of other women didn't experience smashing about men either. A lot of men didn't feel dandy almost men. Even the patriarchs were sick of patriarchy.

Despite this bolus of stance, of feeling, of rage, I was determined to at least try to come up to Manhattan with an open mind. After all, lots of people think of it as Allen's masterpiece, and I was ready to be swept abroad. And I was swept abroad during the opening credits—blackness and white, with jump-cuts timed perfectly, almost comically, to the triumphal strains of "Rhapsody in Blue." Moments later, we cut to Isaac (Allen'due south graphic symbol), out to dinner with his friends Yale (are you fucking kidding me—Yale?) and Yale's wife, Emily. With them is Allen's date, seventeen-year-old high-school pupil Tracy, played by Mariel Hemingway.

The actually astonishing thing near watching this scene is its nonchalance. NBD, I'm fucking a loftier schooler. Sure, he knows the relationship can't last, but he seems only casually troubled by its moral implications. Woody Allen's character Isaac is fucking that loftier schooler with what my mother would call a hey-nonny-nonny. Allen is fascinated with moral shading, except when it comes to this particular result—the event of center-aged men fucking teenage girls. In the confront of this detail issue, one of our greatest observers of contemporary ethics—someone whose mid-career piece of work can approach the Flaubertian—suddenly becomes a dummy (I always hear this word in Fred Sanford'south voice: "dummeh!")

"In high school, even the ugly girls are beautiful." A (male) loftier-school teacher in one case said this to me.

Tracy's face up, Mariel'due south face up, is fabricated of open flat planes that recall pioneers and plains of wheat and sunshine (information technology's an Idaho face, later on all). Allen sees Tracy as adept and pure in a way that the grown women in the flick never can be. Tracy is wise, the way Allen has written her, merely different the adults in the film she's entirely, miraculously untroubled by neurosis.

Heidegger has this notion of dasein and vorhandensein. Dasein means conscious presence, an entity aware of its own mortality—due east.g., almost every character in every Woody Allen movie e'er except Tracy. Vorhandensein, on the other hand, is a existence that exists in itself; it just is—like an object, or an animal. Or Tracy. She'due south glorious simply by being: inert, object-like, vorhandensein. Like the great moving picture stars of old, she's a face, as Isaac and then famously states in his litany of reasons to go on living: "Groucho Marx and Willie Mays; those incredible apples and pears by Cézanne; the crabs at Sam Wo's; uh, Tracy's face." (Watching the film for the get-go time in decades, I was struck by how much Isaac's list sounded like a Facebook gratitude post.)

Allen/Isaac can get closer to that ideal world, a world that has forgotten its noesis of decease, by fucking Tracy. Because he'due south Woody Allen—a great filmmaker—Tracy is allowed her say; she's non a nitwit. "Your concerns are my concerns," she says. "Nosotros have great sex." This works out well for Isaac: he gets to hoover up her beautiful embodied simplicity and he's absolved of guilt. The women in the picture show don't take that advantage.

The grown women in Manhattan are brittle and all too aware of death; they're aware of every goddamn affair. A thinking woman is stuck—distanced from the body, from dazzler, from life itself.

For me, the most telling moment in the film is a throwaway line delivered in a high whine past a chichi adult female at a cocktail party: "I finally had an orgasm and my doctor told me information technology was the wrong kind." Isaac'due south (very funny) response: "You had the wrong kind? I've never had the incorrect kind, ever. My worst i was right on the money."

Every woman watching the movie knows that information technology'due south the physician who's an asshole, not the woman. But that'southward non how Woody/Isaac sees information technology.

If a woman tin call back, she can't come; if she can come, she tin't think.

*

Just as Manhattan never authentically or fully examines the complexities of an quondam dude nailing a high schooler, Allen himself—an extremely well-spoken guy—becomes weirdly inarticulate when discussing Soon-Yi. In a 1992 interview with Walter Isaacson of Time, Allen delivered the line that became famous for its fatuous dismissal of his moral shortcomings:

"The heart wants what it wants."

Information technology was one of those phrases that never leaves your caput in one case you've heard it: we all immediately memorized information technology whether we wanted to our not. Its monstrous disregard for annihilation but the cocky. Its proud irrationality. Woody goes on: "In that location's no logic to those things. You meet someone and you autumn in love and that's that."

I moved on her like a bitch.

Things being what they were that summer, I had a difficult fourth dimension getting through Manhattan—it took me a couple of sittings. I mentioned this difficulty on social media, this trouble of watching Manhattan in the Trump moment. (I fervently hoped it was a moment). "Manhattan is a work of genius! I am done with yous, Claire!" responded a writer guy I didn't know personally. This was a guy who had withstood many of my more than outrageous social media pronouncements, some of which involved my desire to execute and chop up the male half of the species, Valerie-Solanas-like. But the infinitesimal I confessed to having a funny feeling when I watched Manhattan—I believe I said the motion picture was making me "a footling urpy"—this human stormed off my page, declaring himself done with me forevermore.

I had failed in what he saw equally my chore: the ability to overcome my own moralizing and pettifoggery—my own emotions —and practise the work of appreciating genius. Simply who was in fact the more emotional person in this state of affairs? He was the ane storming from the virtual room.

I would accept a repeat of this conversation with many men, smart and dumb, immature and old, over the adjacent months: "You must approximate Manhattan on its aesthetics!" they said.

Another male person writer and I discussed it over dinner one night. It was like a little play:

Female person writer: "Um, it doesn't really hold upwardly."

Male writer, sharply: "What do you mean?"

"Well, it all seems a tad blasé. I hateful, Isaac doesn't really seem too worried she's in high school."

"No no no, he feels terrible most information technology."

"He cracks jokes almost it, simply he certainly does non experience terrible."

"You're just thinking about Before long-Yi—you're letting that color the moving picture. I thought y'all were improve than that."

"I recollect it'due south creepy on its own claim, even without knowing about Soon-Yi."

"Go over it. You lot really need to approximate it strictly on aesthetics."

"And so what makes information technology considerately aesthetically practiced?"

Male writer says something smart-sounding about "balance and elegance."

I wish the female writer had delivered a coup de grâce here, but she did not. She doubted herself.

*

Which of us is seeing more than clearly? The one who had the ability—some might say the privilege—to remain untroubled past the filmmaker's attitudes toward females and history with girls? Who had the ability to watch the fine art without committing the biographical fallacy? Or the one who couldn't help but notice the antipathies and urges that seemed to animate the projection?

I'1000 really asking.

And were these proudly objective viewers really existence as objective as they thought? Woody Allen'south usual genius is one of self-indictment, and here is his one film where that self-indictment falters, and also he fucks a teenager, and that ' south the movie that gets chosen a masterpiece?

What exactly are these guys defending? Is it the film? Or something else?

I think Manhattan and its pro-girl anti-woman story would exist upsetting even if Hurricane Before long-Yi had never made landfall, but nosotros tin't know, and there lies the very center of the matter. Louis C.Thousand.'s I Beloved You, Daddy—a tale of a father struggling to preclude his teenage daughter from hooking upwardly with an older man—will meet a like fate. It will be incommunicable to view outside the noesis of Louis C.K.'s sexual misconduct—if it fifty-fifty gets seen. For at present, distribution has been dropped and the film is not going to exist released.

A great piece of work of fine art brings us a feeling. And withal when I say Manhattan makes me experience urpy, a man says,No, not that feeling. Y'all ' re having the wrong feeling. He speaks with dominance: Manhattan is a work of genius. But who gets to say? Authority says the work shall remain untouched by the life. Authority says biography is fallacy. Authority believes the work exists in an ideal state (ahistorical, alpine, snowy, pure). Authority ignores the natural feeling that arises from biographical noesis of a subject. Authority gets snippy most stuff similar that. Authority claims it is able to appreciate the piece of work free of biography, of history. Dominance sides with the (male) maker, against the audience.

Me, I'g non ahistorical or allowed to biography. That's for the winners of history (men) (then far).

The thing is, I'one thousand not saying I'm right or incorrect. But I'm the audience. And I'yard just acknowledging the realities of the state of affairs: the moving picture Manhattan is disrupted past our knowledge of Before long-Yi; just it's also kinda gross in its own right; and information technology's as well got a lot of things about information technology that are pretty great. All these things can be true at once. But beingness told by men that Allen'due south history shouldn't affair doesn't achieve the objective of making information technology not matter.

What do I do about the monster? Do I have a responsibleness either way? To turn away, or to overcome my biographical distaste and watch, or read, or mind?

And why does the monster brand united states of america—make me—so mad in the first place?

*

The audience wants something to sentinel or read or hear. That's what makes information technology an audience. At the same time, at this item historical moment, when we're brimful in bitter revelation, the audience is outraged freshly by new monsters, over and over and over. The audience thrills to the drama of denouncing the monster. The audience turns on its heel and refuses to see another Kevin Spacey film ever again.

It could be that what the audience feels in its heart is pure and righteous and true. Simply there might be something else going on hither.

When yous're having a moral feeling, self-congratulation is never far backside. Y'all are setting your emotion in a bed of ethical language, and y'all are admiring yourself doing it. We are governed past emotion, emotion around which we arrange language. The transmission of our virtue feels extremely important, and weirdly exciting.

Reminder: not "you," not "we," just "I." Stop side-stepping ownership. I am the audition. And I can sense at that place's something entirely unacceptable lurking inside me. Even in the midst of my righteous indignation when I bitch about Woody and Shortly-Yi, I know that, on some level, I'm non an entirely ethical citizen myself. Sure, I'm attuned to my children and thoughtful with my friends; I proceed a cozy house, listen to my husband, and am reasonably kind to my parents. In everyday human activity and idea, I'k a decent-enough human. But I'm something else as well, something vaguely resembling a, well, monster. The Victorians understood this feeling; it's why they gave us the stark bifurcations of Dorian Gray, of Jekyll and Hyde. I suppose this is the homo condition, this sneaking suspicion of our own badness. It lies at the heart of our fascination with people who exercise awful things. Something in the states—in me—chimes to that awfulness, recognizes it in myself, is horrified by that recognition, and so thrills to the drama of loudly denouncing the monster in question.

The psychic theater of the public condemnation of monsters can be seen equally a kind of elaborate misdirection: nothing to see hither. I'm no monster. Meanwhile, hey, you might want to take a closer look at that guy over there.

*

Am I a monster? I've never killed anyone. Am I a monster? I've never promulgated fascism. Am I monster? I didn't molest a child. Am I a monster? I haven't been accused by dozens of women of drugging and raping them. Am I a monster? I don't crush my children. (All the same.) Am I a monster? I'm not noted for my anti-Semitism. Am I a monster? I've never presided over a sex cult where I trapped young women in a gilded Atlanta mansion and forced them to practise my bidding. Am I a monster? I didn't anally rape a thirteen-year-onetime.

Await at all the awful things I haven't washed. Maybe I'm not a monster.

Merely hither's a matter I take done: written a book. Written some other book. Written essays and manufactures and criticism. And maybe that makes me monstrous, in a very specific kind of way.

The critic Walter Benjamin said: "At the base of every major work of art is a pile of barbarism." My own work could inappreciably be called major, but I do wonder: at the base of every modest piece of work of art, is there a, you know, smaller pile of barbarism? A lump of barbarism? A skosh?

There are many qualities one must possess to be a working writer or creative person. Talent, brains, tenacity. Wealthy parents are good. You lot should definitely try to have those. Just offset amid equals, when it comes to necessary ingredients, is selfishness. A book is made out of pocket-size selfishnesses. The selfishness of shutting the door against your family. The selfishness of ignoring the pram in the hall. The selfishness of forgetting the existent world to create a new one. The selfishness of stealing stories from real people. The selfishness of saving the best of yourself for that blank-faced anonymous paramour, the reader. The selfishness that comes from simply saying what you have to say.

I accept to wonder: maybe I'm not monstrous enough. I'k aware of my own failings equally a writer—indeed I know the list to a fare-thee-well, and worse are the failures that I know I'm declining to know— simply a little part of me has to ask: if I were more selfish, would my work be better? Should I aspire to greater selfishness?

Every writer-mother I know has asked herself this question. I mean, none of them says it out loud. Only I can hear them thinking it; information technology's almost deafening. Does one identity fatally interrupt the other? Is your work making you a less-expert mom? That's the question you ask yourself all the fourth dimension. Merely also: Is your motherhood making you lot a less good writer? That question is a fiddling more uncomfortable.

Jenny Offill gets at this idea in a passage from her novel Dept. of Speculation—a passage much shared among the female writers and artists of my associate: "My programme was to never get married. I was going to be an art monster instead. Women most never become fine art monsters considering art monsters merely business concern themselves with art, never mundane things. Nabokov didn't even fold his umbrella. Véra licked his stamps for him."

I mean, I hate licking stamps. An art monster, I thought when I read this. Yes, I'd like to exist one of those. My friends felt the same way. Victoria, an creative person, went around chanting "fine art monster" for a few days.

The female writers I know yearn to exist more monstrous. They say information technology in off-hand, ha-ha-ha ways: "I wish I had a wife." What does that hateful, really? Information technology means you wish to carelessness the tasks of nurturing in order to perform the selfish sacraments of being an artist.

What if I ' thousand not monster enough?

In a style, I'd been asking this question privately, for years, of a couple male person writer friends I believe to be actually great. I write them both charming emails, but really I am always trying to notice out: how selfish are you? Or to put information technology another style: how selfish do I need to be, to get every bit great as you?

Plenty selfish, I learned as I observed these men from afar. Lock-the-door-against-your-child-while-you're-working selfish. Work-every-day-including-Thanksgiving-and-Christmas selfish. Go-on-book-tour-for-weeks-at-a-time selfish. Sleep-with-other-women-at-conferences selfish. Whatever-it-takes selfish.

*

One recent evening, I was sitting in the chaotic, book-strewn living room of a younger writer and her husband, also a writer. Their kids were tucked into bed upstairs; the occasional yawp floated down from above.

My friend was in the throes of information technology: Her three kids were in form school and her husband had a full-fourth dimension job while she tried to carve out her career freelancing and writing books. A deject of intense literary appetite hung over the firm similar a stormy little micro-climate. It was a work nighttime; we all should've been in bed. Instead we were drinking wine and talking about work. The married man was mannerly to me, by which I mean he laughed at all my jokes. He was tightly wound and overly alert, perhaps because he was non having success with his writing. The wife on the other paw was having success—a lot of success—with her writing.

She mentioned a curt story she'd just written and published.

"Oh, you mean the most contempo occasion for your abandoning me and the kids?" asked the very smart, very charming husband.

The married woman had been a monster, monster enough to finish the piece of work. The husband had non.

This is what female monstrousness looks similar: abandoning the kids. Ever. The female monster is Doris Lessing leaving her children behind to go alive the author's life in London. The female monster is Sylvia Plath, whose cocky-criminal offence was bad plenty, but worse still: the children whose nursery she taped off beforehand. Never heed the bread and milk she ready out for them, a kind of terrible poem unto itself. She dreamed of eating men like air, but what was truly monstrous was simply leaving her children motherless.

*

Perhaps, as a female writer, yous don't kill yourself, or carelessness your children. But you carelessness something, some nurturing office of yourself. When you finish a book, what lies littered on the footing are small cleaved things: cleaved dates, broken promises, cleaved engagements. Also other, more important forgettings and failures: children's homework left unchecked, parents left untelephoned, spousal sexual practice unhad. Those things have to get cleaved for the book to get written.

Sure, I possess the ordinary monstrousness of a real-life person, the unknowable depths, the suppressed Hyde. Just I also have a more visible, quantifiable kind of monstrousness—that of the artist who completes her piece of work. Finishers are always monsters. Woody Allen doesn't simply endeavour to make a moving-picture show a year; he tries to put out a film a yr.

For me the particular monstrousness of completing my work has always closely resembled loneliness: Leaving behind the family, posting up in a borrowed cabin or a cheaply bought motel room. If I can't disassemble myself entirely, then I'1000 hiding in my chilly part, wrapped in scarves and fingerless gloves, a fur chapeau plopped upon my head, going hell-for-leather, just trying to end.

Considering the finishing is the part that makes the artist. The artist must be monster enough not just to first the piece of work, but to consummate it. And to commit all the picayune savageries that prevarication in between.

My friend and I had done zilch more monstrous than expecting someone to mind our children while nosotros finished our work. That's non as bad as rape or even, say, forcing someone to sentinel while y'all wiggle off into a potted plant. It might audio as though I'm conflating two things—male predators and female finishers—in a troubling way. And I am. Considering when women do what needs to be washed in guild to write or make art, we sometimes feel monstrous. And others are quick to depict u.s. that way.

*

Hemingway's girlfriend, the writer Martha Gellhorn, didn't recollect the creative person needed to be a monster; she thought the monster needed to brand himself into an artist. "A man must be a very great genius to make up for existence such a loathsome human existence." (Well, I approximate she would know.) She'due south proverb if you're a really awful person, y'all are driven to greatness in society to compensate the globe for all the awful shit you are going to practice to it. In a way, this is a feminist revision of all of fine art history; a history she turns with a single acid, vivid line into a morality tale of compensation.

Either way, the questions remain:

What is to be washed about monsters? Can and should we love their work? Are all ambitious artists monsters? Tiny vox: [Am I a monster?]

*An earlier version of this article stated that Soon-Yi was a teenager under Woody Allen's care

Claire Dederer is the author of the memoirLove and Trouble. She'south at work on a book near the human relationship between bad behavior and good fine art.

Source: https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2017/11/20/art-monstrous-men/

0 Response to "Hey Guys Its Dangerous Down Here Go That Way Art"

Post a Comment